The GUI control panel is a long standing feature of Microsoft Windows, facilitating granular changes to a vast collection of system features. It can be disabled via Group Policy but is largely available to most user accounts (administrative permissions are required for some changes). From a forensic perspective, we can audit control panel usage to identify a wide range of user activity:

- Firewall changes made for unauthorized software (firewall.cpl)

- User account additions / modifications (nusrmgr.cpl)

- Turning off System Restore / Volume Shadow Copies (sysdm.cpl)

- System time changes (timedate.cpl)

- Interaction with third-party security software applets

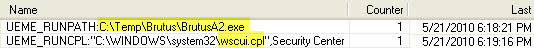

While identifying individual system modifications is difficult, at a minimum we can show that a user accessed a specific control panel applet at a specific time. Context provided by other artifacts may provide further information. As an example, imagine you were reviewing control panel usage on a system and came across Figure 1.

Context is critical, and, while access to the Windows Security Center might not normally be particularly interesting, the fact that it was accessed immediately following the execution of a known (router) password cracking tool might make all the difference.

A Brief Overview of the Control Panel

The Windows control panel is implemented as a series of applets, each represented by a ?.cpl' file. Applets are commonly stored in the %system root%\System32 folder. The system binary 'control.exe' is the control panel application and is used to open applets. However, like many Windows actions, there are a seemingly endless number of ways to access an applet:

- GUI Control Panel

- Start -> Run dialog

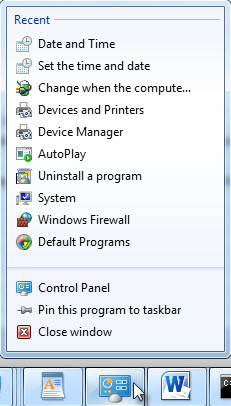

- Task bar (e.g. "Adjust date/time")

- Command prompt (control.exe timedate.cpl)

- Typing "Control Panel" on the Windows 8 start screen

- ?

Unfortunately, different access methods can lead to different artifacts. In some cases, an artifact may not be stored at all depending on the method of applet execution and version of Windows. Luckily, control panel artifacts are recorded in multiple places, and one or more are usually available to identify the activity.

Evidence of Control Panel Applet Execution

Windows Prefetch

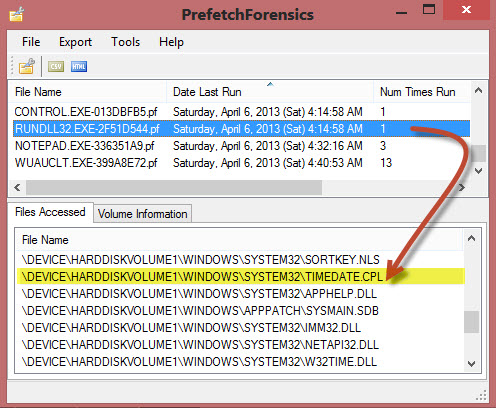

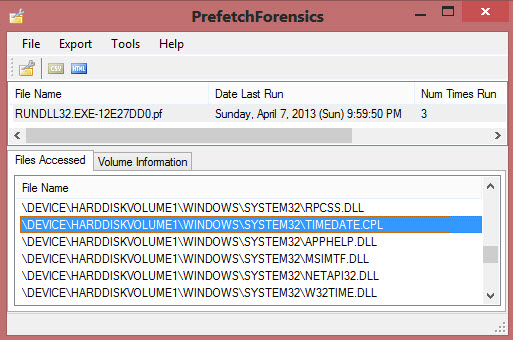

Windows prefetch tracks application execution. Due to the way applets are opened, they do not garner their own.pf file in C:\Windows\Prefetch. It might make sense that Control.exe would provide evidence of applet execution, but sadly its prefetch file only alerts us to the fact that the control panel was opened (and it only exists in certain circumstances). To determine the specific applet executed, we have to dig deeper. If an applet has been executed, one (or more) RunDLL32.exe prefetch files will contain a reference. Multiple RunDLL32 prefetch files referencing the same applet indicate the applet was launched using different methods. This can be caused by case sensitivity used by the prefetch hash computation algorithm (nicely outlined in the Hexacorn blog here). Depending on the applet and how it was spawned, a DLLHost.exe prefetch file may also include a reference. Searching for these references within the myriad RunDLL32 and DLLHost prefetch files can be laborious, but if they exist, you will be rewarded with the first time, last time, and number of times the applet was run on the system.

In Figure 2, information embedded in the RUNDLL32.EXE-2F51D544.pf file tells us that the Date and Time applet was last executed on April 6, 2013 at 4:14:58am UTC and has been run at least once on the system. TIP: While you are poking around in those RunDLL32 prefetch entries, keep an eye out for other system applications of interest such as Microsoft Management Console plugins (i.e. COMPMGMT.MSC). The excellent prefetch tool shown in Figure 2 is by Mark Woan.

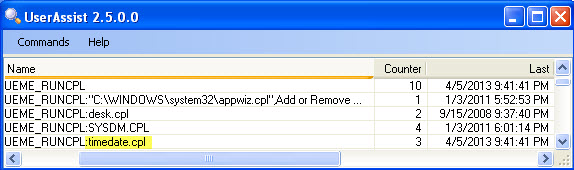

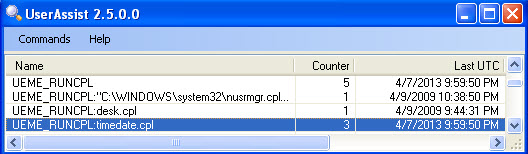

Windows Registry: Userassist (XP/Vista Only)

While prefetch files are one of the more reliable artifacts showing applet execution, a significant drawback is they do not specifically tie actions to a user. Since the userassist key is located in a user's NTUSER.dat hive it allows us to tie activity directly to an account. The full path of the key is:

NTUSER.DAT\Software\Microsoft\Windows\Current\Version\Explorer\UserAssist

Figure 3 shows control panel usage recorded on a Windows XP system. Notice the "UEME_RUNCPL" preface in each userassist entry. This is a unique identifier used within pre-Windows 7 userassist to denote control panel applet execution. In this case, we see four different applets have been run by this user a combined total of 10 times. The time and date applet was last run by the user on 4/5/2013 at 21:41:41 PM. (The userassist tool seen in Figure 3 was written by the inimitable Didier Stevens).

Userassist underwent significant changes with the release of Windows 7. Control panel applet access is no longer reliably recorded within Win7/Win8 userassist. Luckily we can use a unique Windows 7 artifact, jumplists, to retrieve similar information.

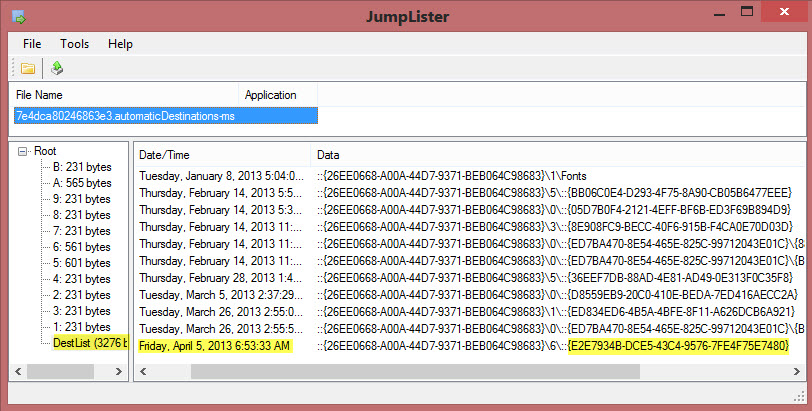

Win7/Win8 Jumplists

Jumplists are one of the more exciting artifacts found in the post-Windows 7 world, and surprisingly even the Windows control panel records information within them. If you aren't including jumplists in your examinations, you need to start. Harlan Carvey has done a tremendous job educating the community on their efficacy and has some great blog posts to get you started.

To gather jumplist information related to the control panel, look for a jumplist named according to the well-known control panel application identifier, 7e4dca80246863e3 (Forensic Wiki). The full path of the jumplist will look like:

%user profile%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Recent\ AutomaticDestinations\7e4dca80246863e3.automaticDestinations-ms

Note that jumplists are unique to each user profile.

Figure 4: Contents of Control Panel Jumplist (Windows 8)

The Windows 8 jumplist contents shown in Figure 4 illustrate an important point. Each control panel applet is assigned a Windows class identifier (CLSID) in the form of a globally unique identifier (GUID). As evidenced in the output from the Windows 8 system here, jumplists use the applet CLSID to record execution. It turns out that {E2E7934B-DCE5-43C4-9576-7FE4F75E7480} is the assigned CLSID/GUID for timedate.cpl. MSDN provides a mapping of applets and GUID associations here. Including GUIDs of interest within your string searches is a recommended best practice. Using this information, we see timedate.cpl was last run on April 5, 2013 at 6:53:33 AM by the owner of this particular jumplist. Unlike prefetch and userassist, we do not get additional information such as first time executed or number of times executed (though leveraging Volume Shadow Copies could provide similar information). The Jumplister tool shown here is also by Mark Woan.

Putting it All Together — Evidence of Time Manipulation

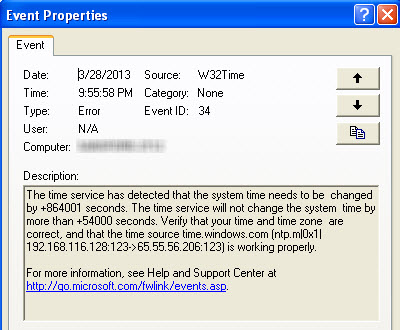

Now let's look at a complete scenario. Imagine during routine event log analysis, you find the following event:

You do a simple calculation and notice 864001 seconds is equal to just about 10 days. Looking at prefetch files last modified approximately 10 days after 3/28/2013, you find the following:

At this point, we have some strong evidence that the system time has been modified. The only remaining question is what user account performed the change? Looking at userassist for the suspect account, you find the final piece of evidence:

TIP: If the system audit policy was set to log successful System Events, you would also see evidence of the time change in your Security Event Log, complete with the user account who made the change.

Well-known forensic artifacts can easily show a user account accessed a control panel applet like timedate.cpl. Proving what changes were made within that applet and why may require additional context. For example, in the case of a user setting the clock backwards to pre-date a contract, we might review control panel usage, event logs, document metadata and file system time stamp anomalies to tell the complete story.

Chad Tilbury, GCFA, has spent over twelve years conducting computer crime investigations ranging from hacking to espionage to multi-million dollar fraud cases. He teaches FOR408 Windows Forensics and FOR508 Advanced Computer Forensic Analysis and Incident Response for the SANS Institute. Find him on Twitter @chadtilbury or at http://forensicmethods.com.