SEC595: Applied Data Science and AI/Machine Learning for Cybersecurity Professionals

Experience SANS training through course previews.

Learn MoreLet us help.

Contact usBecome a member for instant access to our free resources.

Sign UpWe're here to help.

Contact UsHow to approach, research, and develop analytic assessments on emerging technologies and threat trends (Part 2)

“The human mind tends to see what it expects to see and to overlook the unexpected.

Change often happens so gradually that we do not see it or we rationalize it as not being of fundamental importance until it is too obvious to ignore.

Identification of indicators, signposts, and scenarios create an awareness that prepares the mind to recognize change.”

–The Dutton Institute

A Brief Recap

Cyber security leadership, the executive team, the board of directors, and risk management often seek our expert opinion on how an emerging technology or trend will impact the current and future state of business operations, shifts it could cause to the organization’s risk posture, and whether existing security controls are sufficient to manage any new risk or whether additional resources or investment is required. Leadership is also interested in how emerging technology and trends can provide efficiency gains to existing workflows.

The challenge we face when trying to assess the impact of any new advancement is that it often requires a steep multidisciplinary knowledge base beyond that of just cyber security or threat actor tradecraft and trends. In the previous blog post, we introduced this concept of systems analytic thinking, the DIMEFIL framework, an approach to determine market viability, and how to present insights using a common frame of reference. In this blog post, we delve deeper and wider, building our base knowledge on approaches to evaluate emerging technologies and trends, introducing useful structured analytic techniques (SATs) designed to aid in forecasting, and considerations on how to craft assessments such that they resonate with leadership.

Perspective Matters, Link Back to Related Context

All stories require a starting point, a contextual backdrop that acts as a foundation from which the author can build upon. In part 1 of this blog series, we used cyber risk as a well-known reference point that organizational leadership understands. This is one reason why when we craft analytic assessments, we focus on risk concepts like business impact, chance of occurrence, security controls coverage or gaps in existing controls. However, this is not the only frame of reference worth using in CTI—we can also leverage shared experiences of lived through events to draw anecdotal parallels when communicating analytic findings.

Each week there is no shortage of cyber events that occur. Yet as we recount the news headlines in any week, how many, if any, rise to the threshold of signifying an inflection point, some functional shift that changes a natural order? Inflection points can take different forms when we consider cyber innovation and advancements ranging from deviations in a threat actor’s baseline operations, to a new technology platform expanding an organization’s attack surface, to a vendor introducing a security feature to hive off full classes of attacks to the benign—perhaps naive—red teamer that uploads a new framework that just provided adversaries with yet another capability to integrate into its operational arsenal. Since there is such a wide range that could exist for potential inflection points, it’s best we create an organizational schema from which we can ascribe a baseline to identify inflections.

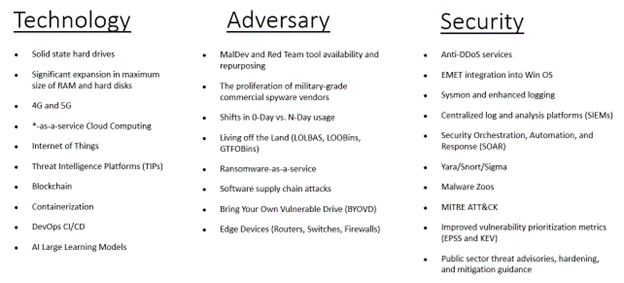

For simplicity’s sake, we will stick with the same model from the first blog post, where we broke cyber risk into three categories: adversary threats and trends, integrated tech stack, and existing security controls. The following graphic represents an illustrative, non-exhaustive enumeration of “cyber” advancements over the past decade grouped into the three categories. Each advancement identified in one of the categories could arguably be considered an inflection point and act as a shared frame of reference from which we can use for comparative purposes to make relative evaluations.

Figure 1: Illustrative Trends and Advancements Over the Past Decade

The interesting part about these advancements is that some of them happened in tandem or short succession of one another. Some may have been spurred or influenced by broader macro-level events like the United States’ Comprehensive National Cybersecurity Initiative or trends like the droves of talented cyber security personnel in the private sector today that largely came from intelligence community, military, or law enforcement cyber careers. In the past decade, we have seen cyber security as a field evolve, branching into burgeoning sub-disciplines.

This outgrowth and fragmentation is one of the reasons I believe newcomers to cyber security struggle at the onset – the core base knowledge requirements have grown commensurately. Individuals with prior backgrounds have incrementally built their knowledge and refactored skills, and they have the depth of understanding to take interrelated and interconnected factors in stride. My buried bottom-line here is that those coming into this new have a steeper learning curve and often a longer journey to internalize the same lessons and understand those interrelated elements. Don’t worry, we’ll provide some guidance on this in the “Where Do I Go To Glean These Insights?” section.

Where to Start

Structured analytic techniques (SATs) are a methodical process designed to help one challenge judgments, create mental models, stimulate creativity, arrange and visualize data, manage uncertainty, and overcome biases inherent to the human mind, amongst other things. In total, there are over 60 different SATs available to assist analysts with critical thinking and problem solving across a range of different problem sets. In their seminal publication, "Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis", Richards Heuer Jr. and Randolph H. Pherson identify six core families of SATs, which others— including the CIA—have distilled into three primary categories: Diagnostic, Imaginative, and Contrarian techniques.

Figure 2: Examples of SATs in Each Category

While this blog post won’t be able to do justice to the full gamut of SATs, a handful of these are particularly useful in helping frame the thought process when forecasting or evaluating potential future scenarios, which includes emerging technology threats and trends:

Putting It All Together

One approach analysts can take when evaluating an emerging technology, advancement, or some other inflection point involves attempting to identify first, second, and tertiary order effects. Said in plain English, what’s the immediate impact followed by longer term effects from downstream dependencies? Answering the 5 Ws and how is also usually a fruitful endeavor as part of this process.

Let’s use a historic, well-known cyber attack as an example to illustrate the various orders of effect it had before providing a technology and a trend focused example.

The 2017 NotPetya case is a good example. The short summary of the NotPetya attack was Russian military cyber operators deployed a wiper to M.E.Doc customers through its update server. The attack was likely designed to only impact Ukrainian organizations. However, at least at the time, any organization with an operational footprint in or that worked with organizations in Ukraine had to choose between M.E.Doc or one other government approved accounting software for tax reporting purposes.

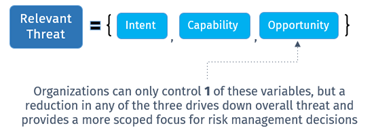

Figure 3: Refresher on the Functional Inputs

IaaS

Edge Device Persistence

Hopefully these questions provide a cursory roadmap to get you started as an analyst. Now let’s pull the findings together.

Documenting Findings in a Compelling Manner

Throughout the intelligence curation process, the AIMS methodology provides a useful framework to conceptualize the story we plan to tell and how we will message the analytic findings. For those unfamiliar with AIMS, it is an acronym that stands for Audience, Issue, Message, and Storyline. There are alternative storytelling frameworks beyond AIMS you might consider like AIM or GAME, but this blog post will only focus on AIMS.

Whether analytic insights are provided in a short form response or using a longer form narrative, a key element to include is its relation to some advancement or innovation that has occurred before. Graphics are an excellent way to convey this type of information on a timeline or creating a compare and contrast graphic. Graphics provide analysts with flexibility to create new mental models, challenge the presentation of an existing approach, or just think creatively and out-of-the-box. So how might we be able to capture broadscale changes in technology platforms and service delivery, shifts in adversary tradecraft, and advancements in cyber security, or perhaps even cyber policy decisions for our leadership team to think through?

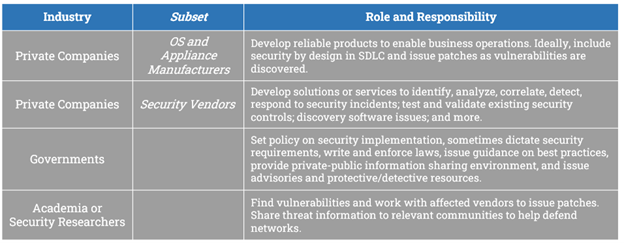

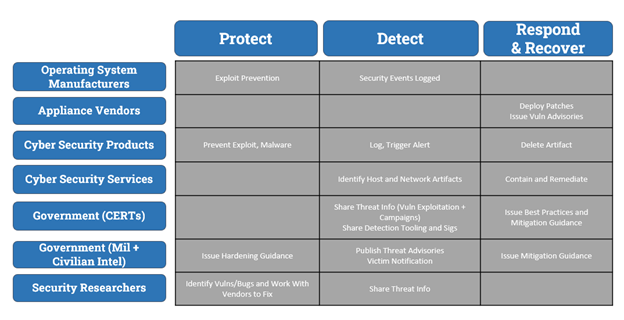

One approach could be to create an ecosystem dichotomy outlining the roles and responsibilities for the various players based on type of organization or what product or service it provides. akin to the table below. With this type of an overview guide in place, we could add a layer on top of it, using a well-known industry schema like NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) to illustrate specific examples of how these players have historically contributed in the past. While there are other ways to approach the problem, in two graphics—albeit text heavy graphics—we have created a foundational base of knowledge that we can build on for our analysis moving forward. The same could be done for showing the usage of wipers over time, evolution of adversary tradecraft, or expansion of targets beyond a particular set of victims for a campaign, amongst others.

Figure 4: Illustrative Example of Roles

Figure 5: Layering Additional Context

Where Do I Go To Glean These Insights?

This is a bit of a chicken or the egg problem. Developing strong critical thinking and problem solving ability is different than gaining an thorough understanding of the cyber threat landscape which is different than proficiency in various cyber security technologies, laws, or policies. While a lot of this can be learnt through self-study and research—and you will likely need to do some of this anyhow—one can shorten the time horizon for knowledge capture by seeking guidance, starting points, and other advice from mentors and other industry peers. Asking about their experiences or their take on a particular topic is another great way to garner their insights as field experts. Analysts, in particular, tend to enjoy pontificating about alternative realities or implications grounded in logic and their experiences.

Conclusion and Path Forward

While there is no magic bullet solution on how to answer a question about emerging technologies and threat trends, this blog series hopefully provided practical guidance on how to frame research and present findings on the topic. In it, we covered concepts designed to improve critical thinking ability and strategic forecasting, examining multi-dimensional effects using systems analytic thinking and frameworks like DIMEFIL/PESTLE. A handful of SATs can help shape our thought process as we work through how we arrived at a particular event, what were the signposts or drivers that got us there, and identifying any indicators we would expect to see. We provided series of questions that analysts may consider using when evaluating an emerging technology or a trend to determine “should I care” and to what extent does this shift status quo. We concluded by covering key considerations when conceiving and crafting the analytic assessment.

This blog series was designed as a primer to jumpstart analytic skills for junior analysts or those transitioning into CTI from a job area. If you are looking for additional practice beyond the forecasting examples we covered in here, I would encourage you to try to answer each of the questions about intent, capability, and opportunity for some of the other advancements listed in Figure 2. Thanks for taking the time to read this blog series.

John has over sixteen years of experience working in Cyber Threat Intelligence, Digital Forensics, Cyber Policy, and Security Awareness and Education.

Read more about John Doyle