SEC595: Applied Data Science and AI/Machine Learning for Cybersecurity Professionals

Experience SANS training through course previews.

Learn MoreLet us help.

Contact usBecome a member for instant access to our free resources.

Sign UpWe're here to help.

Contact Us

Despite Industrial Control System (ICS) environments having a reputation of being relatively stagnant, over the years the industry has seen an accelerating convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT). Primarily serial-based networks running proprietary protocols are increasingly being replaced with ethernet-based networks running TCP/IP protocols. Similarly, "air-gapped" stand-alone networks are being connected to enterprise business networks and the internet. The SANS 2019 State of OT/ICS Cybersecurity Survey found that 34.5% of control networks are connected to the internet and 66.4% are connected to either a third-party private infrastructure or to their enterprise business network. The benefits of increased convenience and reduced costs provided by modern IT functionality, such as interoperability and remote access, serve as a catalyst for IT / OT convergence.

Alone, these changes in the technologies and connectivity of ICS networks might not warrant concern. However, concurrent with this transition, ICS cybersecurity experts are seeing increased targeting of ICS networks by hackers. The same SANS survey found that the percentage of control systems that experienced three or more incidents in the previous 12 months increased from 35.3% in 2017 to 57.7% in 2019 "with the growth in incidents being attributed to foreign nation-states and organized crime where disruption or destruction is the main objective." While the 2010 Stuxnet attack targeting Iran's nuclear program reportedly used malicious USB thumb drives to enter the air-gapped network, modern attacks such as the 2015 and 2016 attacks on Ukraine's power grid or the 2017 attack targeting a Saudi Arabian petro-chemical plant more commonly use initial access and propagation techniques similar to those seen in enterprise IT networks, including phishing and abusing network shares. The relationship between increased connectivity and increased malicious remote-based attacks demand an improved and modernized approach to ICS security.

.png)

Despite this IT / OT convergence and changes in the ICS threat landscape and attack techniques, the perceptions held by those on the front lines of ICS defense may not be adapting accordingly. Among those who have attended an ICS conference or training, there is a good chance that they have been asked to raise their hand to identify whether they identify with IT or OT. In the process of discussing the relationship between IT and OT technicians, it is not uncommon to pick up on contentious undertones and hear half-serious jokes of keeping IT folks away from the ICS network lest they come in and break something. While this distinction may seem to be an innocent way to gauge the background and experience of an audience, maintaining an outdated IT versus OT paradigm may actually pose a risk to ICS cybersecurity.

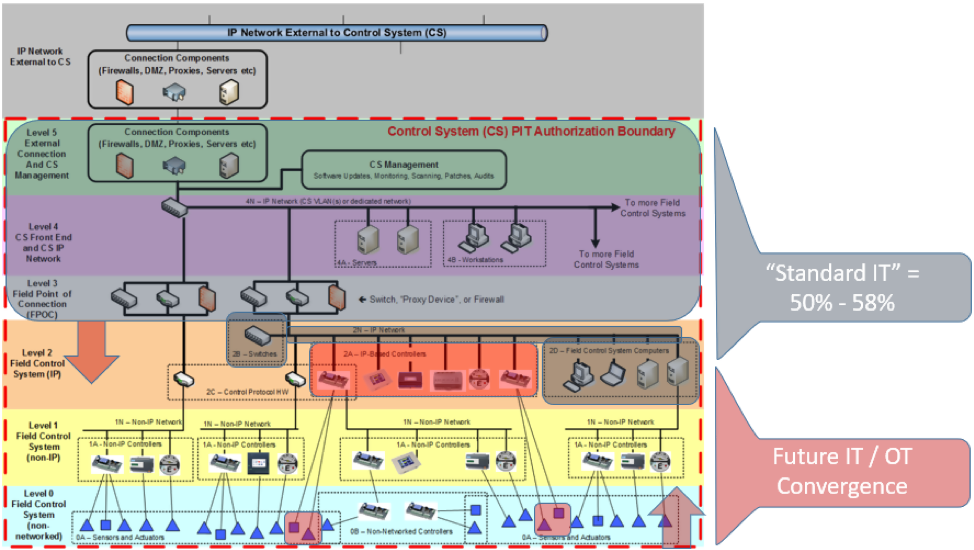

While each ICS network is different, network architecture models function as a useful tool in tailoring and implementing cybersecurity principles. More specifically, they can provide insight into how IT versus OT distinctions are becoming increasingly blurred and irrelevant. In guidance issued to address the cybersecurity of facility-related control systems, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) divides ICS architecture into six levels. At first glance, the DoD's model resembles the six-level Purdue Model for Control Hierarchy widely used within the ICS community. However, a key difference between the two is that while the Purdue model groups and divides devices and subsystems by role or function, the DoD model also considers connectivity and protocol. For example, level 0 actuators and sensors must "not use any form of digital protocol for communication" and the only difference between levels 1 and 2 is that level 1 consists of non-IP field control devices while level 2 is dedicated to those which are IP-based. Immediately following the introduction of their architecture model, the DoD divides ICS devices into "standard IT" and "non-standard IT" components. "Non-standard IT" devices may be correctly understood to be "legacy" OT equipment. Thus, this model provides the ability to quantify the percentage of the ICS architecture represented by IT devices. The image below is the DoD's control system architecture tailored to highlight the levels and components which represent IT.

Even in the minority of ICS networks (per the SANS survey) that are isolated and void of external connections and therefore absent of level 5 altogether, IT still represents half of the architecture. Those who insist on maintaining an IT versus OT paradigm must recognize that the majority of today's ICS networks are predominantly IT. The adoption of IP-based controllers, sensors, and actuators equipped with advanced communication capabilities and functions that more closely resemble IT than legacy OT, means that the representation of OT within the modern ICS architecture will continue to shrink.

As stated in the DoD's guidance, the cybersecurity of the IT components in an ICS network are "largely addressed using standard cybersecurity practices". The document later offers a specific example and states that a level 2 field control system computer proving a "front end" functionality similar to that often seen at level 4 "should be subject to the same controls as a level 4 front end." In other words, an IT device with "standard IT" connectivity and functionality within an ICS network should be secured, as much as possible, with the same controls and principles used in an any other environment. Thus, to properly address the cybersecurity needs of an ICS network, the cooperative expertise of those trained in both IT and legacy OT is required.

An IT versus OT paradigm and a resulting failure to either enlist additional IT expertise or better training existing personnel in IT cybersecurity techniques can manifest itself through the introduction of real-world vulnerabilities. In stand-alone networks, over-confidence in physical security measures may lead to a failure to adopt a "defense in depth" strategy and implement a robust patch management program to mitigate the risk posed by an insider threat. Network devices may not be appropriately configured with a "deny all / permit by exception" policy. Convincing management to proactively invest in application whitelisting or an intrusion detection system is more likely when ICS security operators understand and can articulate the risk associated with their absence.

In order for a paradigm shift to be successful, any enterprise IT expert lacking ICS experience and invited to assist in securing ICS networks must appreciate and guard the trust associated with the assignment. Just as an on-prem enterprise environment is not the same as cloud infrastructure and storing and transmitting medical or financial data comes with unique requirements, it is critical that the unique aspects of an ICS environment be understood prior to implementing change. Even if the future entails ICS networks in which every device down to the actuators and sensors are IP-based components, the physical processes those actuators and sensors control come with unique challenges and safety considerations. Therefore, to see significant improvement in the cybersecurity posture of ICS networks, the paradigm - from all participants - must be one of IT / OT cooperation.

Technology writer Marla Keene works for AXControl.com. In her free time, Marla hikes with her dog Otis or searches for old cameras for her ever-growing collection.

Launched in 1989 as a cooperative for information security thought leadership, it is SANS’ ongoing mission to empower cybersecurity professionals with the practical skills and knowledge they need to make our world a safer place.

Read more about SANS Institute