SEC595: Applied Data Science and AI/Machine Learning for Cybersecurity Professionals

Experience SANS training through course previews.

Learn MoreLet us help.

Contact usBecome a member for instant access to our free resources.

Sign UpWe're here to help.

Contact UsYesterday, I introduced Security Intelligence in the first part of the introduction with some definitions and a rough problem statement. Today, I will get into more details of this domain, beginning with understanding risk and when to apply SI techniques.

JOIN SANS FOR A 1-DAY CYBER THREAT INTELLIGENCE SUMMIT headed by Mike Cloppert - 22 Mar 2013 - http://www.sans.org/event/what...

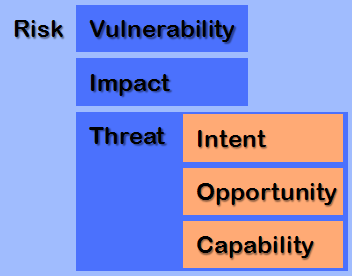

As I like to say, we are in the business of risk management. In order to understand security intelligence, it is imperative that we properly scope and carefully define this concept. Different fields define risk in different terms, but in security, Risk is the product of three primary components: Vulnerability, Impact, and Threat.

Figure 1: Information Security Risk Components.

Vulnerability - Vulnerability is sometimes replaced with "exposure." I would argue that they are represented together as one component. Vulnerability is both mutable and ephemeral. This is good, because it means this component of risk can be affected by individuals and organizations. Applying the principle of least privilege, network segmentation, robust system management, and adherence to software development and life-cycle best practices are but a few high-level examples of how vulnerability (or exposure) can be reduced, with a proportional reduction of Risk. The operative word here is reduced - not eliminated. Again, vulnerability reduction, as you will see, is necessary but insufficient.

Impact -Impact is immutable and changes are either slow or non-existent. This is what happens when security systems fail and the confidentiality, integrity, or availability (but mostly the first two) of data or systems are compromised. This is largely a property of your organization and its operational context - physical, industrial, and what have you. There is typically not much you can do to influence impact.

Threat - Threat is the most important Risk component in intelligence-driven response. In fact, one could say that security intelligence is threat-driven security. To understand, differentiate, and properly respond to threats, it is helpful to divide this concept into a further three components: Intent, Opportunity, and Capability (IOC). These terms are the MMO (Means, Motive, Opportunity) of security intelligence - in fact, they map nicely to one another, but I feel IOC encourages more clarity of thought on Threat.

Intent - Intent stems in a way from impact. It is immutable, and driven by the industry you are in just as Impact is. Typically, at a high level, the intent of adversaries to whom security intelligence techniques are applied is data theft - CNE, if you will. Of course, for each intrusion, each compromise, or each actor, the intent will most likely be slightly different. Is the goal of the adversary to compromise operational details of a campaign, or technical details of a widget? There is nothing that can be done to influence intent.

Opportunity - Opportunity is about timing and knowledge of the target space. In some cases it pairs with vulnerability, but not always. It is one thing to be using a product with a 0-day vulnerability in it, but quite another when your adversary knows this. In other respects, however, opportunity is less related. For instance, wouldn't a company's benefits open enrollment period be a great time for a targeted attack on users using socially-engineered, topically-relevant email as a delivery vector?

Capability - Put simply, capability is the ability of adversaries to successfully achieve their intended goal and leverage opportunity. It is influenced by things such as the skills of the adversaries and the resources (financial, human, and technical) available to them. To extend the 0-day example, a target may be vulnerable, the adversary may intend to steal data by exploiting this 0-day, but if he or she cannot write or obtain the exploit, then the risk is lower.

The "intelligence" in intelligence-driven response is the information acquired about one's adversaries, or collectively the threat landscape. Each industry has a different threat landscape, and each organization in each industry has a different risk profile, even to the same adversary. Understanding one's threat environment is collecting actionable information on known threat actors for CND, whether that action is purely detection or detection with prevention. Now is the time to mention that there is no such thing as protection without detection, or protection without reaction, in this environment. This will be discussed in more detail in Part 3.

By combining information on a threat with observations of activity, one can more effectively and in some cases heuristically defend one's data and systems. Perhaps a heuristic or anomalous event indicative of malicious activity occurs too frequently across your enterprise to respond to it every time it happens. If this maps directly to the TTP of a particular adversary, and you know this adversary's intent is to acquire data which is concentrated in a particular portion of your network, you can investigate the heuristic with this scoping that would otherwise be unreasonable to leverage.

More discretely, discovering the infrastructure, tools, and preferred techniques of each particular adversary, and having processes in place to leverage the data, allows you to detect hostile activity even if all but one minor aspect of an adversary's attempt to break in has changed. Let's take an easy example. If an adversary uses an IP address in an attack, you don't just want to block it at your firewall. You want to detect when it is used in the future, and also not reveal to the adversary that you discovered the attack - otherwise, they'll just switch IPs. You want to let them think subsequent attacks were successful, and then research these attacks for "new" (or "different") techniques, which can then in turn be pivoted on for further defense in case the adversary does ever switch to a new IP.

In this threat environment, you cannot rely on traditional tools like firewalls, IDS, and (especially) anti-virus. These tools can sometimes be leveraged to achieve detection or protection goals, but it will be you that is defining those conditions, based on your security intelligence - not your vendor. These vendors have by and large failed to adapt to targeted attacks, and most are only interested in protecting against the broader, easier problems. This isn't easy, folks, but trust me when I say it's pretty effective.

Key to the success of security intelligence is mapping intent to impact. If your research and compromise response investigations reveal that adversaries are intent on stealing data, then there is little reason to be concerned about denial-of-service attacks from those actors, as the impact of such an activity is completely orthogonal to the goal of a confidentiality breach, and the ancillary goal that is often paired with it, invisibility.

It is also important to understand the threat which is likely behind certain hostile activities. These techniques are not wisely applied to commodity viruses or massive worms - such rigor provides little ROI from an analytical perspective, and tends to waste resources on a problem which can be adequately addressed with existing security tools and infrastructure. Only APT actors should be subject to such scrutiny. Naturally, this creates a derivative challenge: not only must you now identify hostile versus benign activity, but further which of that hostile activity corresponds to APT actors! This needle-in-a-needlestack challenge is at times very difficult, but as you wrap your head around these techniques it becomes easier in some cases. Unfortunately, our adversaries know all too well that they can hide in the cruft, and can (and do) exploit this.

One way to think about this is by answering the question of whether an attack or intrusion is one of opportunity, or intent. Opportunistic intrusions are generally a problem solved by existing best practices (architecture, AV, patching, classic IR model, etc), rather than this analytical offshoot we're calling SI. As that last sentence suggests, it is not the end-all, be-all to CND, but rather one component of a large and complicated affair in information security.

I'm going to take a WAG at how long I'll need to transcribe the large jumble of thoughts in my head onto the computer screen. When it's all said and done, we'll see just how good a guess that is. While in 2 parts, I consider the Introduction to be "Part 1? in aggregate.

Part 2 - Attacking The Kill Chain: Understanding attack progression in the context of incident response. Expect this entry in the next 2 weeks.

Part 3 - Campaign Response: Why your IR model is broken. Expect this entry in the next 3-4 weeks.

Part 4 - User modeling. Expect this entry in 4-5 weeks.

Michael is a senior member of Lockheed Martin's Computer Incident Response Team. He has lectured for various audiences from IEEE to DC3, and teaches an introductory class on cryptography. His current work consists of security intelligence analysis and development of new tools and techniques for incident response. Michael holds a BS in computer engineering and has earned GCIA (#592) and GCFA (#711) gold certifications alongside various others.